Exhibition Feature: "Monument Historique: 19th Century Photographs by Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement and Other French Photographers" at Westwood Gallery, The Bowery, New York (on view through April 5)

Westwood Gallery is currently showcasing photographs by a pivotal yet long-overlooked figure whose work played a crucial role in the early history of photography: Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement (French, 1840 - 1905). Monument Historique: 19th Century Photographs by Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement and Other French Photographers was curated by James Cavello and is an in-depth examination into Mieusement’s highly ambitious, years-long project in which he sought to photograph every important monument, landmark, and building across all of France on behalf of the Commission des monuments historiques (Commission for Historic Monuments). In total, there are over 220 historic sites depicted among more than 580 photographs taken between the 1860s and 1890s. Furthermore, this exhibition is endowed with additional layers of significance: Monument Historique is the first-ever exhibition of Mieusement’s photographs in New York; the first-time his albums have been publicly exhibited in over 100 years; and, this seminal exhibition is part of Westwood Gallery’s roster of special programming celebrating its 30th anniversary. Having visited this exhibition on multiple occasions and spoken with the gallery’s Executive Director & Co-Founder Margarite Almeida and Assistant Director Dana Altman, both explained in great detail how Monument Historique follows a four-fold narrative: 1) Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement as an artist; 2) the advent of photography as a potent form of artistic expression; 3) photography and the importance of historic preservation; and, 4) the incredible rediscovery of Mieusement’s voluminous archive of architectural photographs.

Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement the Artist

Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement was born in Gonneville-la-Mallet in the Normandy region of Northern France in 1840, the year that William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800 - 1877) invented the calotype process - a watershed moment in the medium’s history in which photographic negatives could be made via paper coated with silver iodide. Mieusement’s earliest work in this medium entailed producing photographic details of architectural sites that were part of major restoration projects spearheaded by the esteemed architects Jacques Félix Duban (French, 1798-1870), Anatole de Baudot (French, 1834-1915), and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (French, 1814-1879). 1872 heralded a milestone in Mieusement’s career as he found that photographs of historic sites in the Commission des monuments historique’s archive was only a paltry 600 and had mostly been taken some two decades prior. Alternatively, Mieusement presented a proposal to the Commission in which he articulated the need to photograph every historic site across the whole of France for the sake of preserving the country’s rich and time-honored architectural heritage. Although rejected at first, the Commission later accepted Mieusement’s proposal in 1873. Given the magnitude of the project’s scope and the length of time allocated for its execution, Mieusement had the foresight to practice a tremendous thoroughness in how he would organize his photographs by providing the original negatives, three copies of prints and “to deliver around thirty-five photographs per month over a ten-year period, comprising over 4000 photographs at approximately one hundred fifty thousand French francs” (as explained in the press release). This is precisely why contemporary viewers have the benefit of being able to see Mieusement’s photographs due to the level of preparedness he brought to his work.

Mieusement often wrote of his travels in which he summarized his experiences visiting the myriad cities and villages throughout France, from Avignon and Nice, to Toulon and Moulins. Renaissance-era castles, Rococo palatial estates, Gothic cathedrals, city gates, and vernacular architecture comprise much of the subjects in Mieusement’s albums. Most of these sites are represented from multiple perspectives: interior & exterior photographs, close-ups of structural details (rose windows, tympanums, column capitals, etc.), the site in relation to its surrounding gardens/landscapes, etc.

By 1877, the Commission was so impressed with Mieusement’s steadfastness and the quality of his work that they tasked him with creating 350 photographs for the L’Exposition universelle de 1878, which was focused on restoration projects on select French monuments. He later earned a silver medal for this project and became an honorary member of the French Society of Photography and President of the Society of Artistic Excursions of Loir-et-Cher. Ancillary cultural organizations enlisted the work of Mieusement to photograph more specialized subjects, such as churches, cathedrals, and chapels for the Ministère des Cultes (Ministries of Worship).

It should be briefly mentioned as to who are “the Other French Photographers” referenced in the second half of the exhibition title. The Neurdein Brothers were a pair of photographers who operated a studio in Paris and had been keenly interested in the genre of architectural photography. Much like Mieusement, the Neurdein Brothers captured images of such fashionable and quintessential French sites like L’Arc de Triomphe, King Louis XIV’s bedchamber at the Palace of Versailles, and The Louvre in Paris (shown when it still had a garden courtyard long before I.M. Pei’s Pyramid). Additionally, Paul Robert (French, 1867 - 1898), the son-in-law of Mieusement, was given management of the elder photographer’s archive and collaborated with him in his later projects. Most importantly, Robert was the individual responsible for cataloging Mieusement’s archive and organizing them under the framework of Monument Historique, which became the namesake for this exhibition. Unfortunately, Robert’s work in this regard came to a sudden end when he predeceased Mieusement in 1898.

On September 10, 1905, Mieusement passed away at the age of 65 while residing in Pornic, a commune in the Northwestern region of France.

Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement and the Rise of Photography as an Art

Photography was borne out of the 19th Century. Yet, the early history of photography was fraught with rancorous criticism and impassioned debates on what the medium itself signified for society at large. In 1840, the year of Mieusement’s birth, the revered academic painter Paul Delaroche (French, 1797 - 1856) bemoaned that the existence of photography was the harbinger of painting’s demise, as he infamously exclaimed: “From today, painting is dead!” Even under less forceful terms, there were those who were unconvinced that photography was capable of being used towards artistic ends, a topic pondered in the influential 1857 essay “Photography” by Lady Elizabeth Eastlake (English, 1809 - 1893). By the time Mieusement emerged as a professional photographer, photography was still finding its way as a medium that was caught in a liminality of being part-scientific, part-novelty, and part-documentary - any semblance of artistic value remained along the periphery. And thus, Mieusement’s arrival on the scene could be perceived as that of an underdog since he was working with a medium that had been anything but canonized in Art.

Westwood Gallery wisely incorporated one of Mieusement’s quotes as an enlarged wall text that explains the degree of physical labor that went into capturing his photographs:

Due to the numerous steps required, whether with private individuals to gain access to a window or terrace allowing for the best possible conditions to photograph the building, or with civil administrations to position oneself on the roof of a nearby monument, at times in a gutter, or often, erect temporary scaffold over a public street. All of this, Monsieur Director, involves visits and errands that take a great deal of time.

Moreover, Mieusement had to work with a limited budget and personally transport all of his equipment on foot and via cart, oftentimes under poor weather conditions, especially during winter. Unlike today’s more streamlined camera technology and photographic processes, a 19th Century photographer’s equipment was quite cumbersome to carry. Since photography was hardly an instantaneous process in Mieusement’s days, it would typically take several minutes (in the very least) for a photograph to develop; the development time was slow, and so moving subjects like bustling city crowds and horse-drawn carriages would usually be absent or appear very faintly, almost ghostly. With photography still in its infancy, Mieusement had to take his photographs of architectural sites under the most ideal lighting and weather conditions: clear skies during the middle of the day.

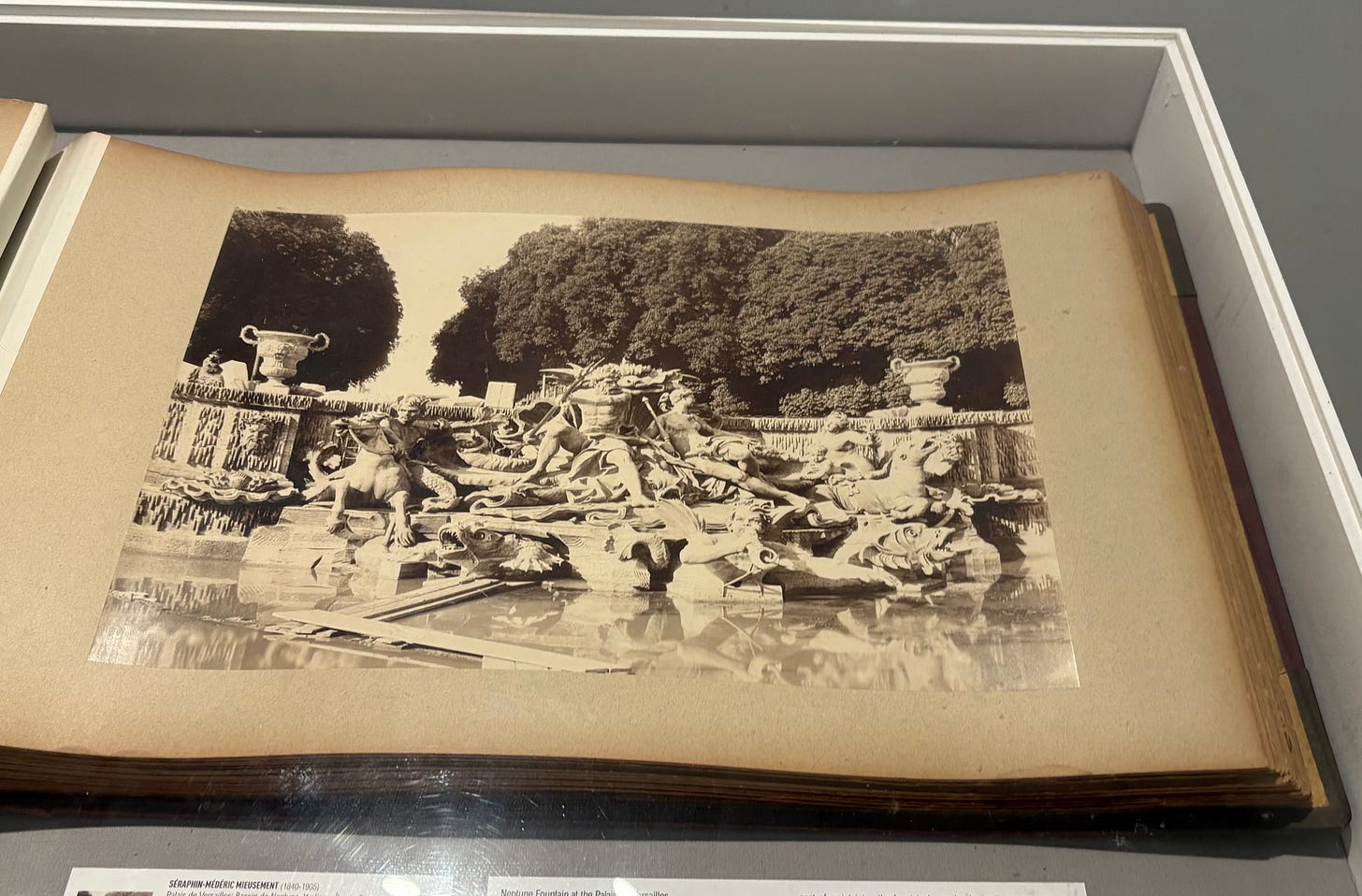

Putting these technical matters aside, Mieusement was aesthetically conscious of how his images should appear, not just in a documentary context, but also in a creative vein. To cite one example, Mieusement’s photograph of the Neptune Fountain at the Palace of Versailles follows traditional compositional methods found in painting in which the ostentatious marble fountain is centrally located within the photograph whilst framed by a background of well-manicured trees. The Rue du Gros-Horloge, a city gate in Rouen that no longer survives, is viewed from a slightly upwards facing perspective to give a sense of height while the flanking rows of shops and residences on either side of the gate reinforce the symmetry of the scene. The corner-facing image of the Chateau de Saint-Germaine-en-Laye’s ornate, multi-leveled facade of arched windows, engaged columns, and brickwork showcases the structure’s sense of uniformity and surface repetition. These are just a few among hundreds of examples highlighting the meticulous compositional strategies Mieusement utilized when factoring how best to portray a specific site in a photograph. In effect, this proficient understanding of scenic arrangement, ideal lighting & atmospheric conditions, and visually arresting aesthetics positions Mieusement as a worthy precursor to the Pictorialists, a late-19th and (more so) early-20th Century movement of photographers who sought to apply the medium toward purely artistic ends comparable to painting.

Compared to the 19th Century, today’s public access to photography - even something as simple and straightforward as a smart phone - is ubiquitous, and one often hears about how far camera technology has come in producing such crisply detailed images. Yet, as Almeida explained to me, the level of detail in Mieusement’s photographs are exceedingly more refined as one of Westwood Gallery’s staff members found that there were more pixels embedded within a single Mieusement image in contrast to a contemporary photograph where the pixel count was less. This explains why one can appreciate the extraordinarily discernible details across the foreground, middleground, and background of each Mieusement photograph.

Architectural Photography and Historic Preservation

The 19th Century was an age when historic preservation became a pressing topic and, in the context of France, this was particularly relevant following the consequences of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars that brought about a wave of destruction to French architecture at the turn of the century. Cultural heritage took on new meaning as governmental and public perceptions of important sites were reconsidered with the growing awareness that such monumental landmarks are subject to irreversible changes. Concurrent with these trends, architectural photography rose as one of the first genres of this new medium. In France, there were a coterie of active architectural photographers, from Girault de Pragney’s (French, 1804 - 1892) images of ancient ruins from various Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cultures to Charles Marville’s (French, 1813 - 1879) photographs of Paris during its citywide renovation under Georges-Eugène Haussmann. However, Mieusement was practically in a league of his own because of the vastness of subjects that he sought out across the country without limiting himself to a niche area or type.

Mieusement’s photographs are gems because they immortalize the structural countenances of prominent sites as they appeared to 19th Century French spectators. Altman remarked on the inherent “truthfulness” that radiates from Mieusement’s images because we, the viewer, are confident of the authenticity of the represented site. In the 18th Century, the capriccio was a popular form of cityscape painting featuring an elaborate menagerie of architectural sites - frequently the most famous and beautiful - in an entirely imaginative display that bore almost no resemblance to their actual views. Photography subsequently came and remedied any doubts about how “truthful” a building or view was portrayed on this new kind of two-dimensional surface. But from a contemporary standpoint, the authenticity of how a site appears in today’s photography can be subject to scrutiny with the intervening usage of Photoshop and other photo-editing software or even the rising influence of Artificial Intelligence (AI). With Mieusement, such doubts are nonexistent.

As it has been made evident about the importance of Mieusement’s architectural photography for the Commission’s much revamped listing of French historic sites, these images are equally demonstrative of how much has changed or remained the same for each site since the 19th Century. In some cases, buildings have undergone major restorations more advanced than what was done 150 years ago, while others have suffered extensive damage (Notre Dame Cathedral and the 2019 fire). In less extreme examples, museums, castles, and cathedrals have different artworks on view or are shown in the days before touristic objects like rope barriers or visible wall texts became commonplace.

Rediscovering Mieusement

Though Mieusement’s contributions to the photographic preservation of France’s architectural heritage was widely recognized during his lifetime, his work fell into obscurity in the decades after his death. However, all of this changed around 2003 when Westwood Gallery’s co-founder & curator, James Cavello, happened upon 13 vintage photographic albums in the home of a wealthy art collector. Surprisingly, these albums were not being presented as having pride of place for they were covered by blankets or cloths and were kept in a closet where Cavello was about to store his coat. Out of curiosity, he perused the albums and became infatuated with their contents. He implored the collector to sell him the albums seeing that there was no intention of exhibiting the works. After a little more persistence, the collector agreed to the sale, but asked Cavello to return the next day to finalize the purchase. Cavello became evermore tenacious about buying all of the albums outright with no delay, no matter how brief. Thankfully, the collector relented and Cavello was able to acquire all 13 albums straight away.

Though instantaneously enamored by the sumptuous images, Westwood Gallery was initially wary of the provenance of the albums and wanted to ensure that the photographs were not national treasures missing from France’s cultural patrimony; if such were the case, the albums would have been immediately repatriated. Soon after, the gallery contacted Bibliothèque nationale de France (The National Library of France) to inquire if the albums were the property of the French government. A representative from the Bibliothèque responded and informed Westwood that the library already possesses the original glass plate negatives of Mieusement … over 6,000 negatives, to be exact. As such, the gallery was encouraged to keep the albums seeing that the original archive was safely housed in Mieusement’s homeland, thus enabling Westwood carte blanche in initiating a long-term research project on the artist’s architectural photographs that ultimately amounted to this exhibition, Monument Historique.

The Exhibition Itself

Since Mieusement has been an understudied figure in the history of photography, much work was required in researching Mieusement’s photography and background prior to conceptualizing this exhibition, hence why Monument Historique was a roughly 20 year undertaking.

As the first exhibition to revisit Mieusement’s work, Westwood Gallery’s approach in conceiving Monument Historique effectively aligned with their mission of “recontextualizing art history”. Mieusement’s photographs are presented in a fresh light - figuratively and literally - in which the exhibition didactics elucidate the ongoing relevance of Mieusement’s role in visually documenting important sites - a theme that remains ever so relevant in the 21st Century, especially when considering the much changed appearance of a still existing site like Notre Dame Cathedral since the tragic fire of 2019. Though the albums are phenomenal records, careful conservation techniques were clearly at the forefront of Cavello’s mind as a selection of the albums are on public display contained in glass-topped cases with a page open to one of Mieusement’s photographs.

Elsewhere, framed modern archival pigment prints of select Mieusement photographs are hung around the gallery to allow one an eye-level perspective in further appreciating the artist’s proclivity for masterfully choreographed architectural photography; there are also a few images of the Neurdein Brothers’ work. The original appearances of these photographs - right down to Mieusement’s signature and accompanying caption for the location name - are preserved to ensure that both the original context and authorship behind the work remains. The choice of printing modern editions of Mieusement’s work was to allow individuals the opportunity to purchase and own a piece of Mieusement in their home.

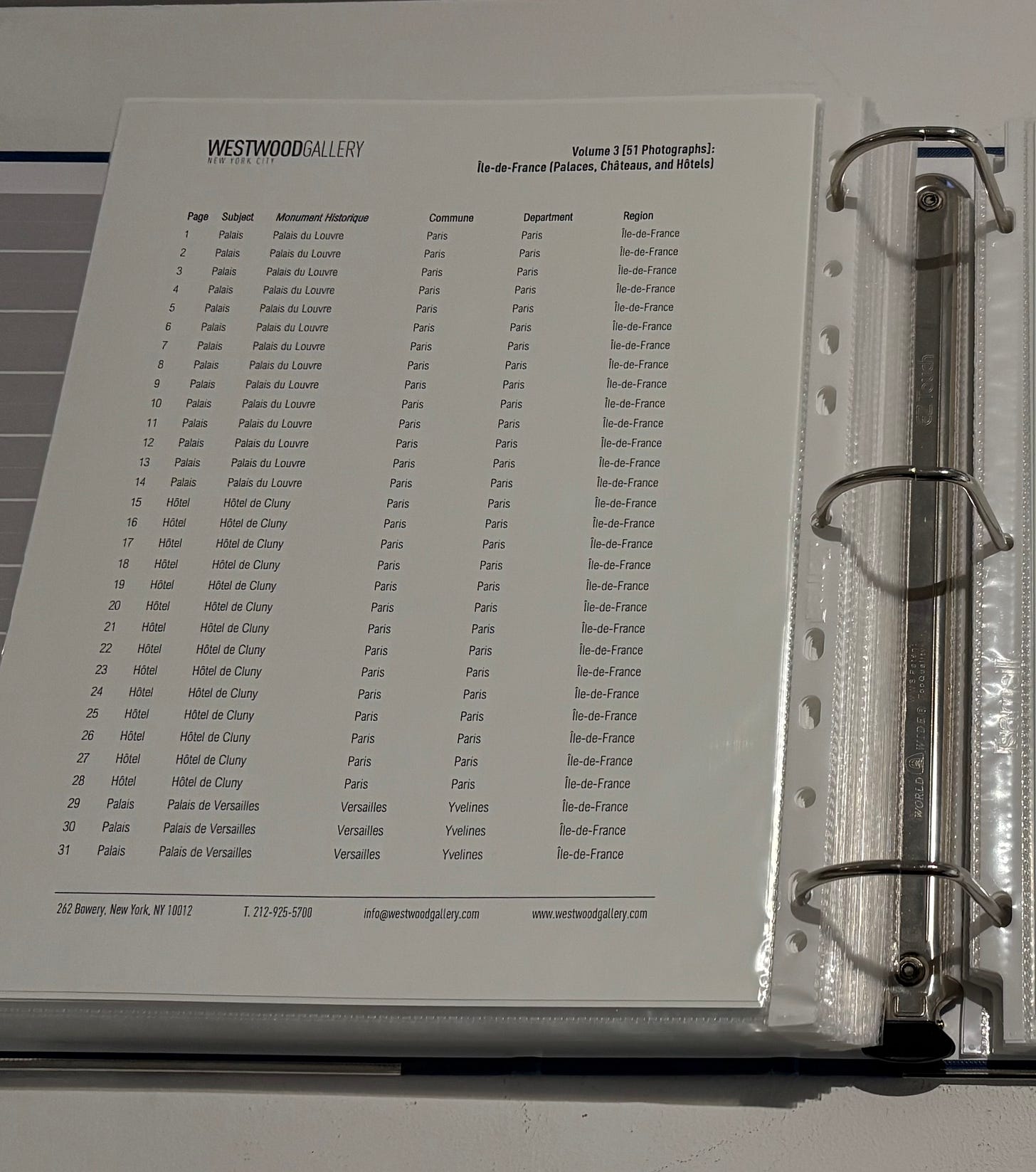

In addition to ample exhibition didactics and contextual timeline, video screens project even more textual information on Mieusement’s photography, the socio-cultural context of his photography & architectural preservation, and high-resolution images of photographs not on display. Viewers have the chance to peruse multiple binders containing reproductions of the more than 580 photographs from Mieusement’s mangum opus.

Conclusion

Mieusement occupies an important position in the history of photography for his adventurous tenacity in documenting sites from every corner of France at a time when historic preservation started to become a serious matter. Simultaneously, his stellar command of proper composition, lighting, and perspective helped to legitimize photography as a viable art form comparable to established two-dimensional mediums like painting and printmaking. It must be underscored that Westwood Gallery’s role in acquiring Mieusement’s albums contributed to a renewed interest in his architectural photographs of France’s glorious sites. Without the interventions of Cavello, Almeida, and the entire staff of Westwood Gallery, a massive lacuna would have remained in photography’s history; considering the original collector did not find much merit in the albums, there is a possibility that, without Cavello’s purchasing, Mieusement’s work would have remained unnoticed and unappreciated. Monument Historique now provides a gorgeous glimpse into every corner of France at a transitional moment between the immediate post-Revolutionary decades and the ascendence of La Belle Époque.

Monument Historique: 19th Century Photographs by Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement and Other French Photographers is currently on view through April 5 at Westwood Gallery, New York.

Westwood Gallery, 262 Bowery, New York, NY 10012

Hours of Operation:

Tuesdays - Saturdays: 10am - 6pm

Sundays & Mondays: Closed

Fascinating to learn about this under-appreciated photographer..