History in the Making and History Made: "The 55th Anniversary People’s Flag Show” at Judson Memorial Church, Greenwich Village (November 9 - 15, 2025)

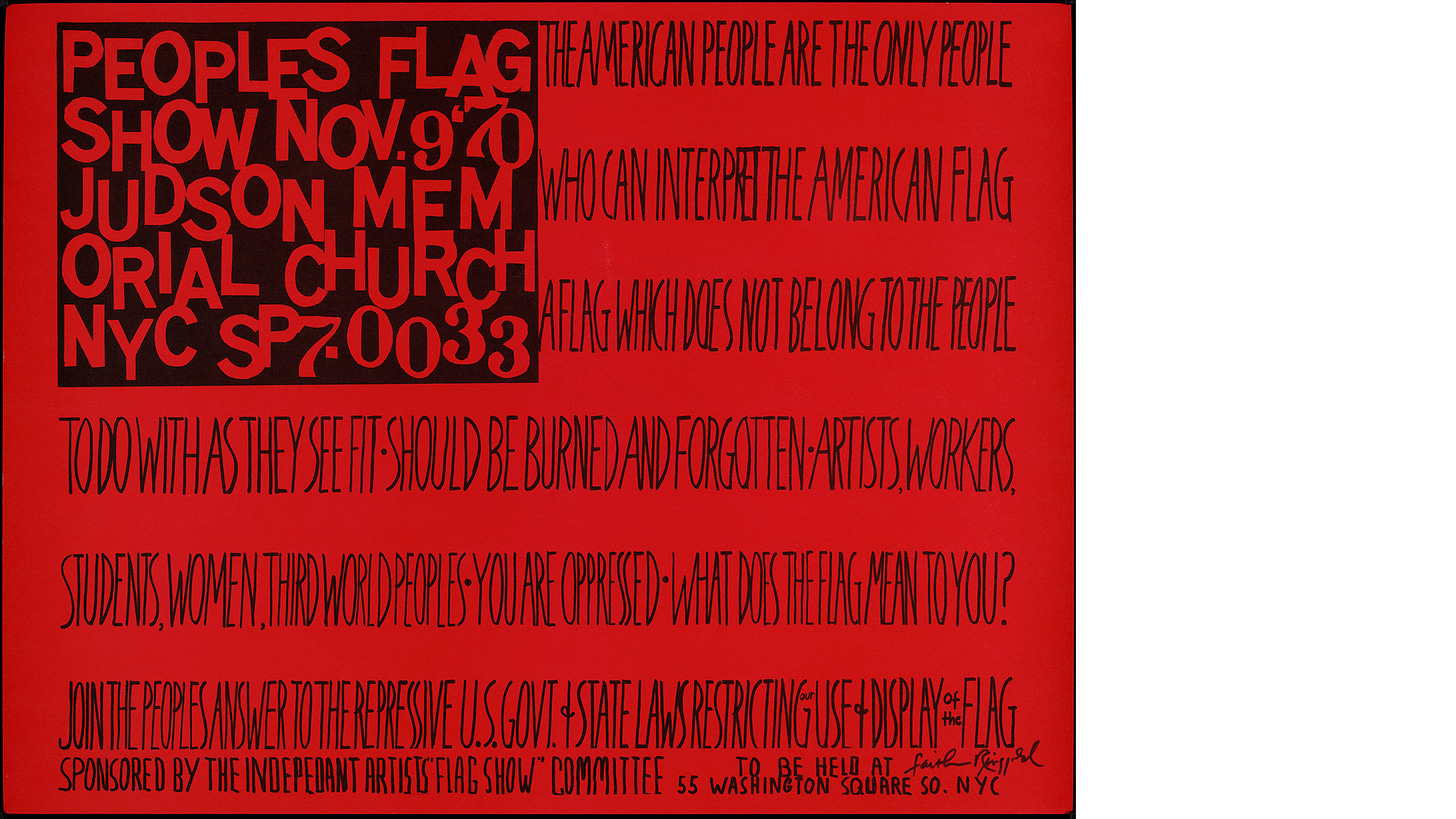

It isn’t everyday that you get to experience an exhibition that is a direct successor to an earlier, historically significant one. Such was the case for a show that entered my purview through a few artist friends who sent me an invitation a few weeks ago - The 55th Anniversary People’s Flag Show. In November of 1970, an exhibition was held at Judson Memorial Church as a political mobilization effort in protest of the then-ongoing Vietnam War. Site specificity of the exhibition is integral to the story of this show as Judson Memorial Church is an historically significant building that is closely associated with avant-garde art, postmodern dance, and social justice activism; Judson lies squarely in the nexus of the Greenwich Village / Downtown New York sphere, hence another integral layer to its countercultural sensibilities.

Much like today, the occurrence of the first Flag Show was during the Republican presidency of Richard Nixon, a polarizing figure whose leadership was closer to despotism than democracy (the man literally had an enemies list - a far worse crime than Watergate). Censorship was on the rise and young, peaceful protesters were murdered at Kent State University in Ohio by members of the National Guard. Sound familiar to a certain orange-hued someone? This exhibition was supposed to occur five years ago, but alas, 2020 and the height of COVID-19. With the political landscape in much more dire straits today than 5 years ago, the 55th Anniversary exhibition was even more timely.

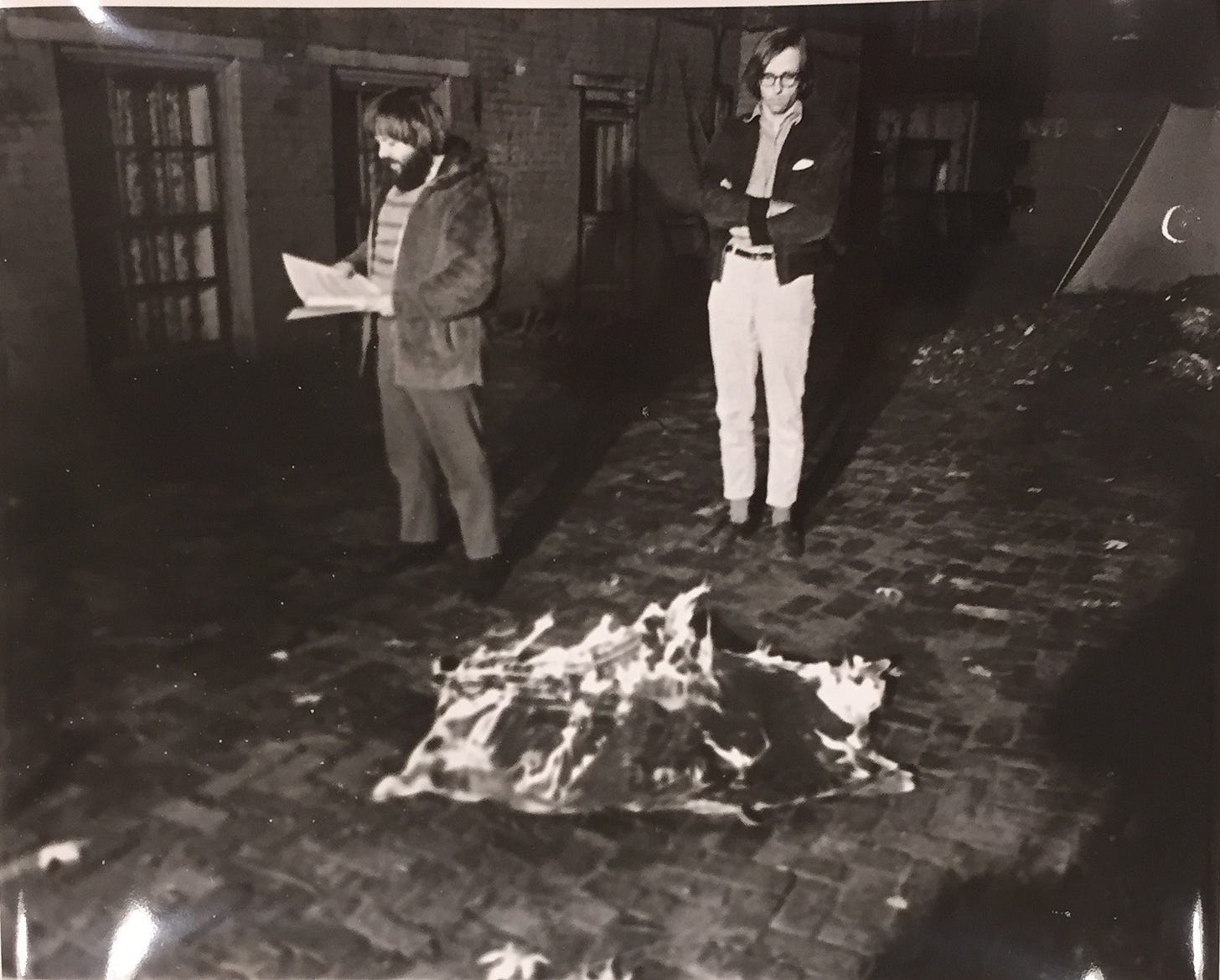

Around 150 artists participated in the 1970 exhibition, many of whom have since passed on: Faith Ringgold (American, 1930 - 2024), Kate Millett (American, 1934 - 2017), Jean Toche (Belgian-American, 1932 - 2018), et al. Given the freneticism of American political life in the early-1970s, a police raid interrupted the show and three of the organizers - Ringgold, Toche, and Jon Hendricks - were arrested and charged with desecration of the American flag.

With the exception of a few returning artists (including Jon Hendricks), the 2025 show encompassed a remarkably diverse body of artists reflective of the much changed political and demographic landscape of the United States a little over half a century later. The 2025 iteration was a worthy successor to the earlier exhibition as its entire programming - both the expected and unexpected - was very much in the spirit of late-1960s & early-1970s agitprop protest and performativity. Additionally, as is the case with any avant-garde movement, there was also the element of internecine conflict in which purported institutional values (Judson Memorial) clash with that of an artist (I will address this point more fully later on).

The basement-level of Judson served as the main exhibition space in which American flag-themed artworks were splayed everywhere, in some instances hung from the wall as you would find them in a school or municipal building, others dangling from the ceiling, some on tables, a few screened in moving image works, and the rest on the floor. A huge facet of American exceptionalism dictates that the American flag is an infallible symbol that is essentially treated with godlike status. What I loved about this show (and the same applies to the historical revisiting of the 1970 exhibition) is that it proved the American flag is simply a manmade form of political iconography. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but so, too, is meaning. Each of us - in the broad collective of the term - have our own interpretations of what the American flag signifies - for better or for worse, depending on the person with whom you speak (and their political persuasion!).

The artists represented in this exhibition were extremely varied, not only in medium or how they engaged with the theme of the American flag, but also in their stature as artists. There was a healthy mix of seasoned, regularly-exhibiting artists; those who used to exhibit frequently, but have not participated in many shows recently; and, lastly, first-timers and emerging artists.

The curation of the individual works was accomplished to tremendous effect by Alexis Rai, whose curatorial vision strategically gave voice to a range of artists who each had much to say through word, visual expression, and performance.

A hand-crafted version of the American flag made from pieces of cardboard and vinyl was strewn on the floor. A fallen flag? That was my initial interpretation. Well, I was taken by surprise in the most chaotically pleasant way possible in the middle of the opening night. The artist entered the space, knelt down, ensconced himself in the makeshift flag, and proceeded to violently toss his body, scream & shout, and thrash himself here and there. All of this occurred while people were milling about, chatting, and looking at the works. One visitor purportedly was about to call security, until I found out that the curator and possibly one or two other people were aware that this performance was supposed to happen in this spontaneous way with absolutely no public announcement beforehand that it would occur. I was enthralled because it elicited authentic reactions - as the artist crawled out of the room, an old woman in the doorway looked confused as to where she should make her next move without getting in the artist’s way. The frenzied performance was definitely the closest I may ever come in my life to fully understanding what one of Nam June Paik’s action music performances would have been like or Joseph Beuys walking into a gallery and smashing a piano to bits, all in an act of purported spontaneity (at least, from the viewer’s perspective).

Photographer Prinny Alavi brought gender and sexual politics in the mix through a massive, blown-up photograph of a nude woman whose face is covered by her long blonde hair as the menacing hands of an unseen man reach out from behind to fondle her breast and grope her vagina. An American flag is entangled around her, with part of its creases appearing from under the woman’s neck while the rest emerges from below the vagina. She wields a sword in one hand and a stuffed teddy bear in the other. The history of America - its conquest - has been one of unceasing sexual violence … from Columbus’s rape of Indigenous women and the violence inflicted upon enslaved African-Americans, to gendered & sexual repression in the 20th Century all the way through to our current President who openly celebrates his grossly debaucherous lifestyle (let’s also not forget the metaphorical rape of the land with Manifest Destiny, often represented under the guise of a personified America as a woman).

Multidisciplinary artist Arlene Rush made use of a real American flag for her submission. The flag is draped over a hung piece of squared wooden framing whose edges contain the repeating text: WE THE PEOPLE. The work was hung from one of the exposed pipes in the basement, and the dilapidated, worn appearance of the wrinkled flag conveyed a mournfulness that the ideals of what the American flag is supposed to symbolize - freedom, equality, hope, peace, etc. - have been irrevocably lost and cast aside like a piece of garbage.

I was especially pleased to see that Faith Ringgold’s spirit lived on in this exhibition as her famous print from the 1970 show was included as a reminder for younger generations of her decades-long contributions in fighting for social justice in the United States.

Other worthy mentions to include: Rafaelina Tineo & James Mutton’s textile-based messaging in which a graduation cap & gown are marked with somber messages like “You may kill my body” and “The flag is mourning”; Laura Sue King’s painting of an American flag reconfigured as a bullseye shooting target (like Jasper Johns, but with more potent interpretational value attached to it); Anthony PRZ’s queer-centric representation of gay love during the American Revolutionary War; Chihiro Ito’s packaged reduction of the American flag as a consumer good; Phoebe Luff’s sculptural miniature of what appears to be a periscope in which the tattered remains of an American flag filter through (a critical lens on American war and imperialism was the first association that sprung to mind), among several dozen other examples in this show.

Since I was only able to visit the show on the first and final nights, I later became aware that one artist was excluded from the finalized Open Call. Gwendolyn C. Skaggs - an artist, activist, and IPV Coercive Control Advocate - submitted a painted cardboard sign emblazoned with the red & white stripes of the American flag that was labeled over with the Jewish Star of David in blue, punctuated in the center by the imposing blackened figure of the Nazi swastika. Surrounding the recognizable symbols was the following text in bold capitals: STOP U$RAEL HOLOCAUST OF PALESTINE (the lower register of the sign with “Palestine” was represented with burning flames); underneath this was a line of text in Arabic. I just so happened to run into Skaggs on the last day of the show and was not completely aware of the whole backstory behind her exclusion from the show, but later learned that Judson Memorial has a clause that prohibits the usage of the swastika in any content.

Initially accepted by the church, Skaggs later received a last minute rejection - not by the curator - but by the Senior Minister Rev. Micah Bucey. Skaggs even brought in photographic evidence from the original 1970 exhibition in which an artist incorporated the swastika as a critical stance on American exceptionalism through a manipulation of the white stars. She stood outside of Judson each night with her artwork in protest of the rejection on the grounds that the message behind her work was precisely in line with the values of Judson through a demonstration of “radical social justice seeking, and unfettered, uncensored creativity” (Rev. Micah Bucey’s word-for-word description of the show’s intent).

The story of Skaggs’s piece in relation to Judson Memorial has strong parallels to the furor surrounding the late Canadian artist Philip Guston’s paintings of the Ku Klux Klan that were originally supposed to exhibit on a nationwide museum tour in 2020, but were ultimately rescheduled to 2024. Like Skaggs, Guston used painting as a means to excoriate racial violence through a satirical and, at times, overtly condemnatory lens.

The 55th Anniversary People’s Flag Show most definitely lived up to and possibly even exceeded the hype of the original 1970 show, not in a competitive sense of which show was better, but because of the calamitous political moment in which our country has found itself. It was all the more appropriate that this show was revisited, not in the space of a museum or gallery, but that of Judson Memorial in furtherance of what the church stands for as a space of political activism and creative expression to be seen and heard by every kind of individual.

Thanks so much for including my work in this insightful article. Btw Judson accepted all the submission from all the artists and I think that is what at the last minute Skaggs piece wasn’t noticed till it was installed. The last min rejection of the piece is as you had said comparing it to Gustons piece Much to think about since art does open up conversations on the hard topics